AI & Learning from Luddites

Have you ever encountered the term ‘Luddite’ before? If so, you’ll know it’s often used derogatorily to describe people who resist technological progress, synonymous with being backward, out of touch, and quaint.

Well, what if I told you this perception of the Luddites is a vast oversimplification and the product of a deliberate propaganda campaign? In fact, I would attest that these people from the early 19th century have a lot to teach us about the labour impacts of AI.

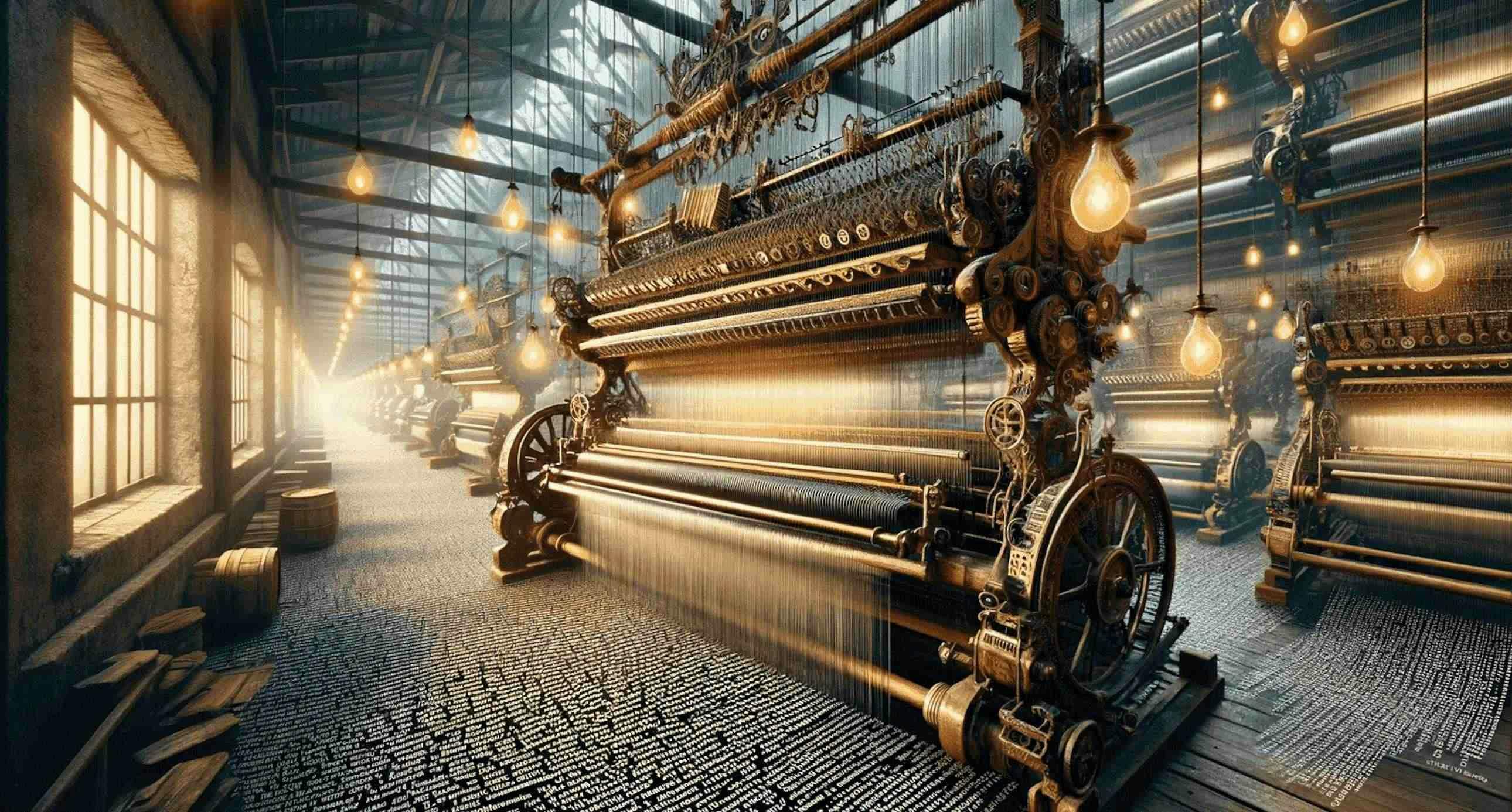

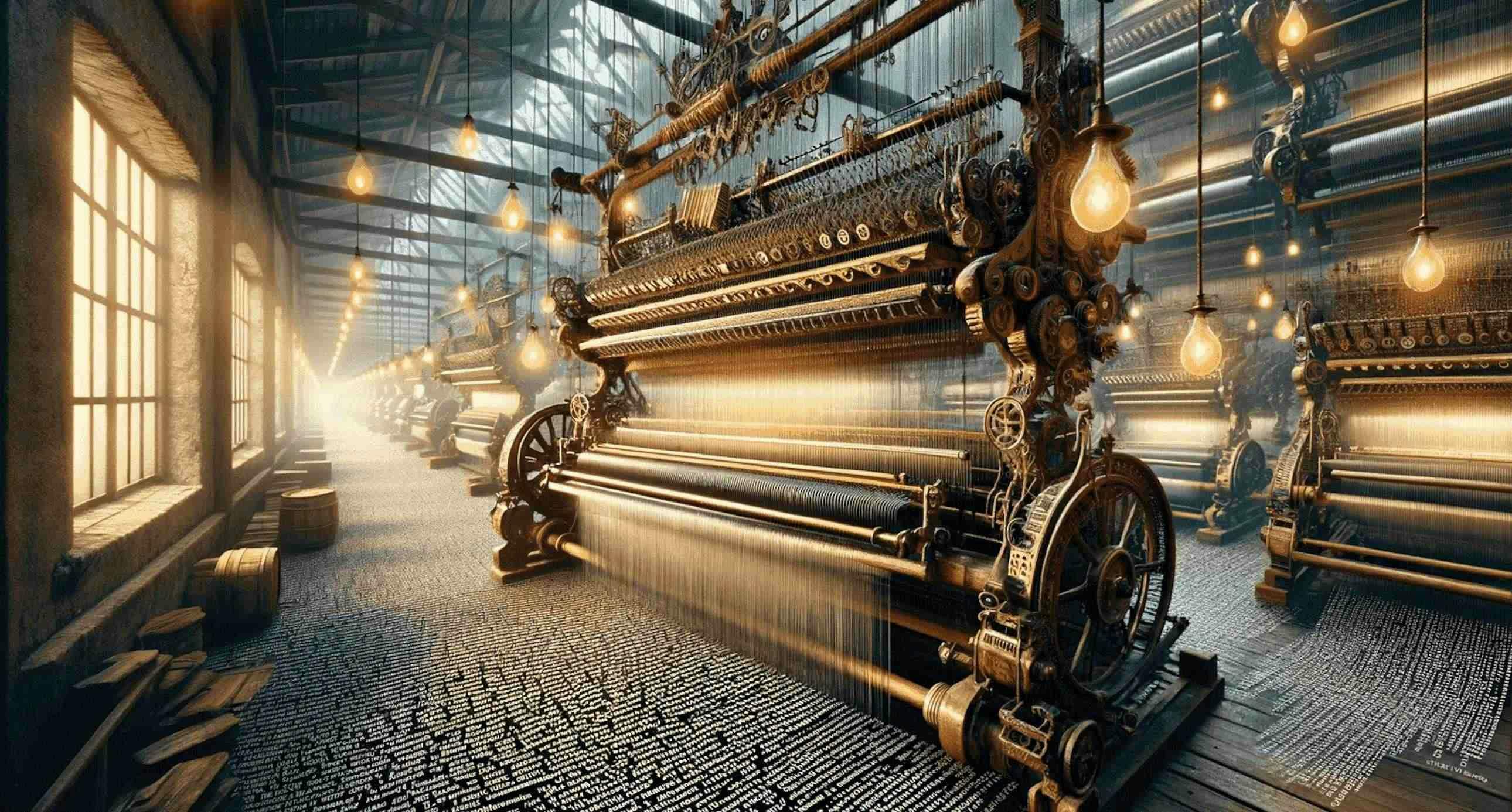

The better we understand labour movements the more informed our human resources decisions become, so please join me for a brief walk through this interesting time in history. Between 1811 and 1816 the Luddite movement grew notorious for protesting and smashing weaving machinery. At this time in history the industrial revolution hadn’t yet picked up steam, and the idea of factories and capital being the primary source of economic production was just taking root. Unions were illegal, democratic institutions were limited, and social programs began and ended with the woefully inadequate Poor Law.

Newly invented weaving machines allowed the wealthy who owned them to produce fabric at a rate never before seen. This sounds like a great achievement, but it was detrimental to nearly everyone else in society.

-

The novelty of the technology combined with a focus on quantity over quality, meant that the factory fabrics were riddled with low uniformity and durability issues. Clothing which would once have lasted years, now fell apart in months.

-

The price of fabric dropped dramatically. Factory owners knew they simply needed to move enough volume to make a profit, even if their goods were shoddy. This meant that traditional artisans producing quality fabrics suddenly found themselves unable to make a living from a once essential cottage industry.

-

Finally, the labour of making fabric didn’t go away with automation, it just became much much worse. A vocation which was once held by skilled artisans making a good living working from the comfort of their own homes was replaced in no small part by unskilled orphans working for poverty-level wages in extremely unsafe factories.

So, the Luddites, inspired by the myth of a man named Ned Lud, who allegedly smashed his weaving machine after being beaten for not working fast enough, rose up, marched, and brought their hammers.

The Luddite movement was decentralised, and the name Ned Lud served as a rallying cry for the dispossessed. Factory owners would find letters nailed to their factory doors stating that if they didn’t cease the use of their ‘obnoxious machines’ they would be paid a visit by Ned Lud’s army. Many factory owners found out the hard way these letters were not to be ignored, and fear spread among upper society. All the while these marching Luddites were supported and cheered by the working class.

Fearing a similar revolution to what had just occurred in France, the British government’s response to the Luddites was swift and ruthlessly uncompromising. They passed the Frame Breaking Act in 1812 making the breaking of weaving machines punishable by death, deployed soldiers to protect the interests of factory owners in numbers exceeding those deployed to fight Napoleon, and orchestrated a widespread propaganda campaign which still shapes our perception of Luddites to this day.

Now, while an interesting topic in itself, how do these Luddite protests relate to present day workers and AI?

Like the weaving machine was to fabric, generative AI models are now able to produce immense amounts of content. Articles, art, music, and, increasingly, videos are all now available for the low low price of a prompt. This automation revolution is producing abundantly and driving the cost of content to near zero.

As a result, we now find ourselves saturated in cheap content, but are we better for it?

Copywriter voices are increasingly becoming drowned out as our news feeds fill to bursting with derivative takes and repetitive styles. Many artists, designers, and writers are finding themselves suddenly out of work, or watching their compensation backslide. And like with the weaving machines of old, this automated content does not come without the need for human labour, it’s only that the nature of this labour has again gotten significantly worse. Often overlooked, generative AI models require human training to refine their outputs. This training is repetitive, low skilled, and low paid. Rather than orphans in factories, we now have gig workers in developing countries working for as low as $8 dollars a day to prop up incredibly wealthy tech companies. This is not even mentioning the numerous products of human labour these models are trained on.

While cloud AI doesn’t present much for workers to smash, that hasn’t stopped people from trying. Data poisoning tools like Nightshade are used to change pixels in uploaded art such that it ‘poisons’ any image generation model trained on them, breaking the model’s outputs in chaotic and unexpected ways. I am not advocating for such actions, but these efforts to undermine the progress of AI easily parallels the Luddite protests.

As we navigate this new era of generative AI, it's crucial to remember the Luddites' true struggle wasn't against technology itself, but against its use to benefit a few at the expense of many. If generative AI is the 21st century's weaving machine, let's ensure we learn from history. Wherever we can, we should collectively strive to integrate generative AI into our economy with more compassion, ethics, and equity than was present in 1811.